One of the key objectives we’ve set for ourselves, is to build what we hope to be ‘the definitive’ list of names of musical pieces written, or in some cases arranged, by both Thomas Bulch, and George Allan. Sounds easy?

Each of the two composers presents their own particular problem in this respect. In this blog post I’ll write about the problems faced when trying to achieve this for George Allan’s work.

With both men, previous researchers have made a good start in understanding this. In George Allan’s case a good list was compiled by Robert Wray, who was king enough to provide us with his findings comprising a list of over 40 marches, and then Steve Robson (now part of this group). Roy Newsome, a respected academic in the field of brass music, claimed in his work “Brass Roots” that to his understanding there were 52 marches composed by George, whilst elsewhere I have seen estimates of as many as 70. In addition to this there were pieces of dance music (Roy Newsome understood there to be 18 in “Brass Roots”) and an unknown number of overtures and fantasias. The information that was out there gave us a good starting list to be going on with, but what then.

The best way to be sure you have a genuine title by a composer is to find copies of the music score itself. George Allan compositions usually have a couple of identifying features that help indicate their authenticity. Firstly his name would usually be shown as ‘Geo. Allan’ and secondly pieces would usually feature one of two addresses where we knew he lived. “2 Pears Terrace” or “4 Osborne Terrace”. Incidentally the presence of either of those helps us to understand whether a piece was published pre, or post, 1925. One of the key issues that we face is the age old problem that while things are ‘current’ the holders of such property don’t always see the value in them, so many of the original old documents are lost, possibly as the paper lost its integrity over time, or was damaged. There isn’t a great deal of the original music score in circulation. There are a number of collections in libraries and archive collections, some of which are well catalogued. Which was a great place to start, and indeed that led to a few more names of pieces that we didn’t have. The National Brass Band Archive in Wigan had a few names in their catalogue, of which we weren’t aware. We found a piece called “Gabriani” for sale on eBay. Wright and Round had a number of pieces for sale in their archive collection. The National Library of Australia had a few pieces we hadn’t heard of before, and were kind enough, for a fee, to digitise them for us. The British Library has a couple of pieces we hadn’t seen listed (we’ve not seen them yet, but plan to go take a look at the end of April). I even reached out to a band or two based upon a lead printed online, including our new friends at Kirkbymoorside who managed to share “Belmont” with us. However, once we’d exhausted all those options, what next?

Whilst looking into T E Bulch I’d noticed that the Australian press in the late 1800s had been exceptionally detailed in reporting the activities of brass bands, and notable figures of the brass band scene. In many ways the ‘goings on’ of the brass bands that were in attendance at just about any public event of worth, were ‘of interest’ particularly with the local pride at stake in the contesting scene. On the flip-side, with brass bands depending largely upon philanthropy and fundraising it’s probable that the committees behind the bands would take great pains to show how hard the bands were working to justify the donations provided to ensure their upkeep. What was commonly reported though was the programme of music that was, or would be played, at each performance, usually with the composer of each piece included respectfully.

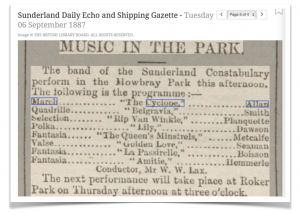

The usual format I found is – Type of music; “Name of piece” (Composer) as in this example below

Trawling these for references of Thomas Bulch seemed to be productive, so I took out a subscription to the British Newspaper Archive to see if I could find anything by George Allan. Initially I was looking for mentions of Allan himself and, though I found a few, his seemingly modest nature and lifestyle revealed little. There were mainly mentions of his appearances as contest adjudicator. However when I, and by this time Brian, took to hunting possible George Allan compositions in brass bard programme listings it didn’t take too long before we were finding names of pieces we’d not seen before. When that happens it’s always exciting, like finding another clue in a mystery.

Not Altogether Straightforward.

It hasn’t entirely been straightforward, though. There have been a number of things that have thrown us off the rails along the way. Typical problems include:

- The quality of Optical Character Recognition (OCR) in newspaper archives – technology is great but not faultless, and part of the nature of these old newspapers is that they have faded print, quite old fonts, may be creased when scanned – there are a number of reasons why the original newspaper image might not have converted the image accurately to text for searching. In many ways this just makes the task more fun, like a detective work game. To be fair there is always the opportunity to correct the text when you find relevant references, though I have to confess to not always doing this, mainly as a result of time constraints.

- More than one Allan – in 1881 the population of Britain amounted to around twenty four and a quarter million people, so you can imagine that in among there there were quite a few George Allans. It was a common enough name in Victorian times for Thomas Bulch to find himself employed, in Australia, by an entirely different George Allan to the one he had grown up alongside. How many George Allans were composing brass music, or working as a bandmaster? I don’t know for sure, but the problem is worsened when the composer’s name is listed only as ‘Allan’? What gives you a good degree of confidence when you find a piece named is when the name provided is “Geo. Allan”, yet even then it’s not ‘bullet proof evidence’. To see “G. Allan” as the composer is useful, but more often than not we just see “Allan”. And that’s when you start to have niggling doubts and start to look for other clues. Overall there are aspects about a reported name that can still increase the likelihood of it being ‘our’ George Allan. One typical clue is if the piece is listed in a programme along with another piece we recognise and know to be the Shildon George Allan. Otherwise, there are subtle patterns in the titles of George Allan pieces. Ones named after places particularly. None of that is entirely robust though, so to a certain extent yo have to go with the balance of probability until you can prove or disprove it. One particular “Allan” that occasionally crops up in my findings is Ernest W H Allan – the British Library contains many pieces of his score, and though he seems mostly a composer of popular piano pieces there do seem to be cases of brass bands playing his compositions. Another George Allan I often find was a bandmaster from Berwick-upon-Tweed, though, despite being reported as being of high regard, he doesn’t appear to have been a composer.

- Human error in reporting – it seems that journalistic lack of attention to detail, that so many still bemoan today, was no better in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This has led to my finding George’s name sometimes by accident as it has been listed as ‘Allen’ with an ‘e’ – or I may have found a piece that is definitely George’s such as “Knight Templar” attributed to an “O. Allan” or suchlike. It’s easy to do I’m sure, and could often be a result of mishearing, or misremembering. I am quite certain that I have found pieces listed that have not been George Allan’s but have been misattributed to him – one example I recall being “The Old Rustic Bridge”, which was actually written by Eric Walton. That said, sometimes composers would come up with the same title unknowingly. The best way to mitigate such findings is, when finding evidence of a new piece in a newspaper, to try to qualify it by finding more, though that’s not always possible.

Overall, it’s not always easy or straightforward, but at least finding titles of piece attributed in this way gives you a hypothesis – something to seek to prove or disprove. I think, though in the listings that we provide, I may have to provide an indication as to whether we ‘think’ or ‘know for sure’ that a piece was created by our featured composers. I shall look to make that amendment at some point soon.

For the future, what we’d really love to do, when we think we have found all there is to be found, is contact all the band librarians in the UK and ask what they have in their libraries. It would be great to run that as a national survey and see just what’s still out there and put it all on a big map to see where George reached nationally.