I enjoyed looking into Sam Lewins so much that I felt another ‘sidetracked’ piece was in order, about another interesting supporting character in the story of how New Shildon’s bandsmen influenced the Victorian brass scene. This time I want to look a little closer at the man without whom the story could have been so very different. Imagine if Thomas Edward Bulch hadn’t gone to Australia, but stayed at home and created all that music in Shildon alongside George Allan. Imagine if the tune to “Waltzing Matilda” had been entirely different. Imagine a world where great Australian brass pieces like “Flowers of Australia”, “The Battle of Eureka” and “Austral” hadn’t been created. Imagine that Bulch’s Model Band had been formed in Britain instead of Ballarat. That would be imagining a world in which…. there never was a John Malthouse.

I enjoyed looking into Sam Lewins so much that I felt another ‘sidetracked’ piece was in order, about another interesting supporting character in the story of how New Shildon’s bandsmen influenced the Victorian brass scene. This time I want to look a little closer at the man without whom the story could have been so very different. Imagine if Thomas Edward Bulch hadn’t gone to Australia, but stayed at home and created all that music in Shildon alongside George Allan. Imagine if the tune to “Waltzing Matilda” had been entirely different. Imagine a world where great Australian brass pieces like “Flowers of Australia”, “The Battle of Eureka” and “Austral” hadn’t been created. Imagine that Bulch’s Model Band had been formed in Britain instead of Ballarat. That would be imagining a world in which…. there never was a John Malthouse.

John Malthouse was born in April 1860 and was ten months old by the time of the 1861 census. His parents, George Malthouse, born in 1839 and Ann Malthouse (nee Applegarth) born around 1836, were married at Heighington on 29th October 1859. George, the son of a family of farm labourers, was born at Aycliffe, and after his rudimentary education learned the skills of boilersmithing in the railway engineering industry, and hence was drawn to New Shildon – whereas Ann originated from nearby Heighington. George’s father had come to the area from Barton, Yorkshire.

As well as John, Ann bore three more sons for George; Thomas in 1863, George in 1864 and Robert William in 1869. Though Robert was a little younger the three older lads were very much contemporaries of both Thomas Edward Bulch and George Allan and all would have been educated together at the small British School on Station Street that had been founded by the Stockton and Darlington Railway.

As was so often the case in that age, though, the fragile integrity of family wasn’t to last. George Malthouse died on 31st October 1870 leaving Ann a widow with four sons to raise. The family had lived in Alma Road, but by In 1871 the family had moved to Soho Street and Ann as a widowed head of the household took in lodgers to help make ends meet. This appears at the time to have been common, and not difficult as the demand for labour locally outstripped the availability of accommodation. Most houses in this small clutch of streets that sprang up around the railway wagon works were small and overcrowded. It would have been a difficult existence, particularly bearing in mind that a reliable supply of fresh water only came to the Shildons in 1868. What’s somewhat strange in the 1871 census is that Ann’s son George Jr. isn’t living at New Shildon with his brothers but instead is living, aged 7, as a lodger with a family at Great Lumley where the head of the household was one John Cowens, a farmer. It’s not clear why.

On the 26th April 1873 Ann Malthouse remarried. This time to a John Abdale Gascoigne at New Shildon. John, born in the nearby market town of Darlington had come to the town from Wolsingham, in Weardale, to work as a labourer. His mother, like Ann, was a widow too. He initially lodged with the Fleming family on Railway Terrace. Joseph Fleming, an engine driver, had married Hannah, John’s sister, so John was effectively lodging with family.

John became stepfather to the Malthouse lads, but the boys retained the surname of their natural father. They were all young bandsmen learning to play under the tutelage of Thomas Bulch’s uncle, Edward Dinsdale. From what was to happen in the following years you get the sense that John Malthouse must have built up a strong camaraderie with the young Tom Bulch throughout this childhood.

For reasons that are obscured in the mists of time, the Matlhouse family decided to seek their fortunes elsewhere. There were opportunities to be had in Australia and the government of the day were keen to strengthen the British presence in that territory, but whether the Malthouses were incentivised is unclear. However on 30 June 1879 John Gascoigne, his wife and the four sons all travelled to London where they boarded the steamer ‘City of London’ as steerage passengers to travel to Australia via Plymouth and St Vincent.

The steamer ‘City of London’ had been built in 1863 to be operated by the Inman Fleet to be part of the Liverpool and Philadelphia Steamship Company transporting passengers to the United States. They had in 1853 been the first company to offer transport to steerage passengers (who initially were required to take their own food) at a cheaper rate. Steerage passengers made up 80% of the Inman line’s passengers. The City of London weighed 2550 tons gross weight and was propelled by a three bladed iron screw propeller. The ship was mostly black with a single funnel and three masts in case she ran out of coal. It was sold in 1878 to William Ross and Co. Thistle Line and fitted with new engines. Though it was listed in the Australian press as being a ship of the Orient Line. This sale leading to being repurposed to transporting passengers and cattle to and from the US and Australia.

Above: The “City of London” depicted in its heyday for the Inman Line

A report on the ship arriving into New York in the year it was launched describes the vessel in excellent detail.

“She is constructed on the most approved principles, with all the recent improvements as to both build and machinery, measuring 355 feet in length on deck, by a breadth of 40 feet 4 inches in beam, with a depth of 26 feet. She is about 2,466 tons gross measurement, and is 1,678 tons register, and is propelled by engine, of 550- horse power, which can be worked up to 1,500. The motive steam is raised by four boilers, heated by twenty furnaces, fitted athwart-ships from the centre, the furnace and engine-rooms being kept cool and sweet by an admirable system of ventillation. It is calculated that these twenty furnaces will consume about sixty tons of coal per day, by which agency it expected that the vessel will attain a speed of about fourteen knots an hour.

The City of London is very strongly framed, and is divided into six water-tight compartments by five strong iron bulkheads, which extend from the keel up to the upper deck, thus receiving great additional strength, and being secured in a high degree from dangerous accident from either water or fire. She is further strengthened by steel water-tight deck stringers, which extend in breadth from the bulwarks to the house on deck, throughout the whole length of the vessel; and besides this security, still greater firmness and tension are insured by her sheen strake being of double steel plates from stem to stern.

Besides her powerful propelling machinery, she is also fully equipped as a sailing vessel, having three tall masts, is ship-rigged, carrying large square as well as fore and aft sails.

On deck she has a wide and lofty house, which extends from the stem right aft to the stern, the roof of which forms a spacious and magnificent promenade deck. To the extreme aft of this is the wheel-house. Immediately in front of the wheel-house are the Captain’s cabin and first officer’s room, and between the officer’s rooms and the engine-room is the saloon or main cabin, an exceedingly elegant and beautiful apartment, sixty feet long by eighteen feet wide, very fully lighted and ventilated by side lights, and fitted up in a style of luxurious and tasteful elegance.

Directly forward of the saloon are the steward’s pantry and bar, which are furnished with a profusion of elegant and beautiful silver-plate, porcelain and crystal.

The staterooms for the saloon passengers, 52 in number, capable of accommodating 120 passengers, are under the main-deck – spacious, well lighted, and, like every other portion of the vessel, most carefully ventilated, by side openings and air shafts. The portion on this deck, forward from the engine-room, is devoted to sleeping apartments and mess-rooms for the second and third-class passengers. These apartments also are well lighted and admirably ventilated. The closet and other sanitary appliances of the ship are ample and complete. The ship is supplied with eight life and other boats, two very large ones being fitted with CLIFFORD’s lowering apparatus. She has also numerous life-buoys and apparatus for preventing and extinguishing fires.”

It all sounds rather grand, though I suspect that the 450 third class ‘steerage’ passengers including the Malthouses would have experienced little of the ships ‘finer points’ during their 54 days on board.

They arrived at Melbourne around midnight on 23rd August 1879 after what was reportedly an agreeable passage. Passengers were quarantined on arrival, during which period a number of cases of measles broke out.

Interesting to note the fate of the ship itself – which disappeared at sea in November 1881 along with 41 people, on her last journey back to London.

The Malthouse lads maintained their interest in brass music and between the age of 19 and 24 he had worked his way up to being bandmaster of the Kingston and Allendale band. Renowned Victorian band authority and historian Robert Pattie tells me a little bit about Allendale in those days. “It’s hard to imagine Allendale having a brass band as there is practically nothing there now but it was gold that brought hundreds of people to the area and there would have been hundreds of tents set up. A temporary city of thousands of people”. Another slight note of curiosity and coincidence in the tale is that there is an Allendale not that far away from Shildon, and that New Shildon Saxhorn Band’s first bandmaster Robert De Lacy was bandmaster there for a time.

We are told that he also during this period maintained correspondence by letter, probably the only option at the time, with Tom Bulch back in Shildon. This is quite remarkable when you think about it. These days we can send an e-mail around the world in seconds. A letter can be carried by plane quite quickly, but the mail was carried by passenger ships (which also carried news of events in the world – when the Malthouses arrived the newspapers were buzzing with news from The Cape which had also arrived on the ship). This meant that a letter might take about 60 days to arrive and the response might take just as long. There would be a need for much patience.

Whatever John Malthouse said to Tom Bulch in those letters was enough to convince the young Tom Bulch, and three of his fellow bandmates, that his future lay over the oceans. We are told that John, perhaps knowing his own limitations as a bandmaster, and having great respect for the emerging talent of his childhood friend, offered Tom his position in the Kingston and Allendale band. Tom’s grandson Eric Tomkins also suggests that there was something about the offer that Tom Bulch must have felt offered better prospects for his health; though whether Bulch had a medical condition is not recorded anywhere that we have seen so far. Perhaps it was just the tantalising lure of an adventure.

Whatever it was, Tom Bulch, Sam Lewins, James Scarffe and Joseph Garbutt left Shildon, seen off at Shildon station, according to one newspaper report, by between two and three thousand admirers and well wishers. John Malthouse was to have his wish fulfilled.

When Thomas Bulch and his three travelling companions from Shildon arrived in Australia in 1884 it was John Malthouse that came to greet them. As promised, he arranged for Bulch, as an experienced brass bandmaster, to take control of the Kingston and Allendale Brass Band. Furthermore he and his brothers played their part in whatever band Bulch then went on to control for a few years. When Thomas Bulch resigned from the 3rd Battalion Militia band at the beginning of 1887, and formed Bulch’s Model Band (that would become the City of Ballarat brass band), the Malthouse boys seem to have been at his side. In his writings, Jack Greaves, the Australian band historian, recognised the Malthouse brothers as having been prominent bandsmen on the Victorian circuit.

On 23rd January 1888, the Ballarat Star reports “Bulch’s Model Band, who have entered for the Sydney Centennial competitions, leave Ballarat by the 7.10 p.m. train this evening for Melbourne, en-route to New South Wales. The contests will commence on Wednesday. At 6.30 this evening the Model Band will muster in front of the Star office, and will next march up Sturt street and along Lydiard street to the Western railway station.” the article then goes on to name the band members taking part, so we learn that on that occasion Thomas Malthouse would play soprano cornet and John would play solo tenor horn.

There are a couple of particularly telling measures of the friendship between John Malthouse and Tom Bulch. The first is that when Tom Bulch married Eliza Ann Paterson of Glendonald Australia in the district of Creswick Plantation on 8th April 1885, John Malthouse was a witness to the marriage. We can see this from the marriage certificate.

More significantly, we also know that John and Thomas chose each other to be business partners. On November 21st 1885 an announcement appears in the Ballarat Star as follows;

“Music, Music, Music – Messrs BULCH and MALTHOUSE have great pleasure in announcing to the public at Ballarat and surrounding districts that they have opened a MUSIC WAREHOUSE in Bridge Street opposite the market. PIANOS, ORGANS and HARMONIUMS, and every description of Musical Instruments kept in stock. Sheet Music, Music Books, Tutors, &c. Note the address- BULCH AND MALTHOUSE, Music Warehouse, Bridge Street, Ballarat.”

The music store provided an income, but also offered Thomas a channel through which to sell his compositions: brass, military piano and otherwise. Bulch published his own music under the name of the Bulch & Malthouse business, with the printing being done by F W Niven & Co. He was able to try to realise an ambition to dedicate his life to making and teaching music, free from the shackles of a manual occupation. In time, a second store was opened in Maryborough to the north of Ballarat when John Malthouse moved there.

26th March 1889 saw an incident that Tom Bulch’s grandson, Eric Tomkins, tells us changed the relationship between the two men. The Advocate (Melbourne) reported the story thus: “In Sturt Street, Ballarat, on Tuesday night, the warehouses occupied by Mr. Bulch, music seller, and Mr. Reardon, boot importer, were totally consumed by fire, together with their respective stocks; Mr. Sander’s shop was insured for £150, but the stock was not, covered. Mr. Reardon was not insured, but Mr. Bulch has a policy over his stock for £450. The fire broke out in a small room at the rear of the music warehouse.” Thomas lost much of his early manuscripts and private papers in the fire and it changed the viability and fortunes of the business. After the fire Thomas obtained space in a sports store that was opposite the burned out premises. The new business was in the name of Bulch only. We are led to understand that Bulch and Malthouse had fallen out. When Thomas later moved to Albury he started a new store there under his own name. Whether the strength of friendship between the two ever returned is not told.

In Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia during 1892 John Malthouse married Margaret Ann Porter. The couple would go on to have three daughters – Dorothy Ann (1894 Maryborough), Eunice (27 July 1903) and Vida Louisa (1899 – Allendale).

The Malthouse men continued to have connections to Bulch’s Model Band even after it ceased to be controlled by Thomas Bulch, who had left Ballarat for Melbourne in 1891. Jack Greaves tells us that John Malthouse, having previously set up a Malthouse’s Model Band in Maryborough, took over as bandmaster of Bulch’s band too in that year. John’s brother Robert Malthouse played Cornet in Bulch’s Model Band and also became bandmaster for a brief time around 1900 as explained by the Ballarat Star on Oct 20 1900. (James Scarffe was the conductor). Reportedly there must have remained some association between Bulch and Malthouse as we’re told that the Model Band did not want to lose Bulch’s influence entirely and appointed him as an instructor to the band so he could continue with them in that capacity. As Bulch’s influence on the Ballarat band gradually waned, the Malthouses also played a part in the transition of that band to being the City of Ballarat Brass Band. George Malthouse played Bb bass for the City of Ballarat Brass Band for some years. It also appears as though on occasions John Malthouse played Tenor Horn with the City of Ballarat Brass.

Above: John Malthouse in a 1909 line up of the City Of Ballarat Brass Band (second row, fourth from right)

Of John Malthouse’s music shop in Maryborough it seems that the business did not fare well. The Argus of Melbourne tells us on 24th August 1895: “Notice to creditors – Notice is hereby given, that John Malthouse, of High Street, Maryborough, in the colony of Victoria, music seller, has by deed dated the twentieth day of August 1895, conveyed and assigned all his estate, property, and effects, whatever and whosoever, to Frederick Wooton Danby upon trust for realisation and otherwise for the benefit of the creditors of the said John malthouse, as in the said deed mentioned. All persons having any claims against the estate are hereby requested to send in the same an particulars thereof to Messieurs danby, Butler and Fischer, accountants and trade assignees, 66 Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, the trustees agents, the the ninth day of September 1895, after which date the trustee will distribute the trust fund between those persons only of whose claims he shall have notice.” In short, John malthouse was Bankrupted.

A funeral notice of 26th June 1913 tells of the death of Ann Gascoigne, John’s mother who was buried that year at the Ballarat New Cemetery. On the occasion of her funeral the cortege left her son John’s residence of 207 Dawson Street.

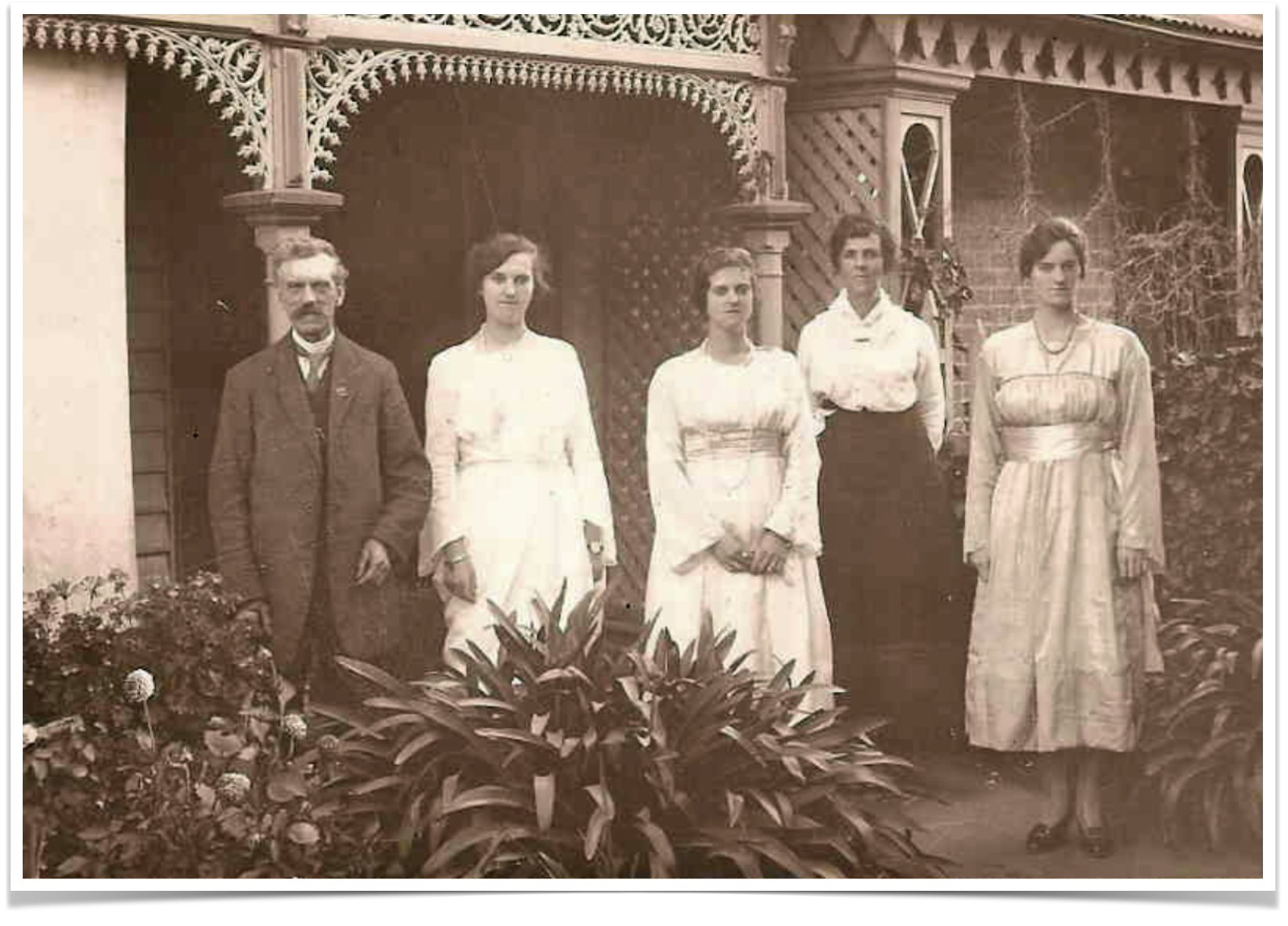

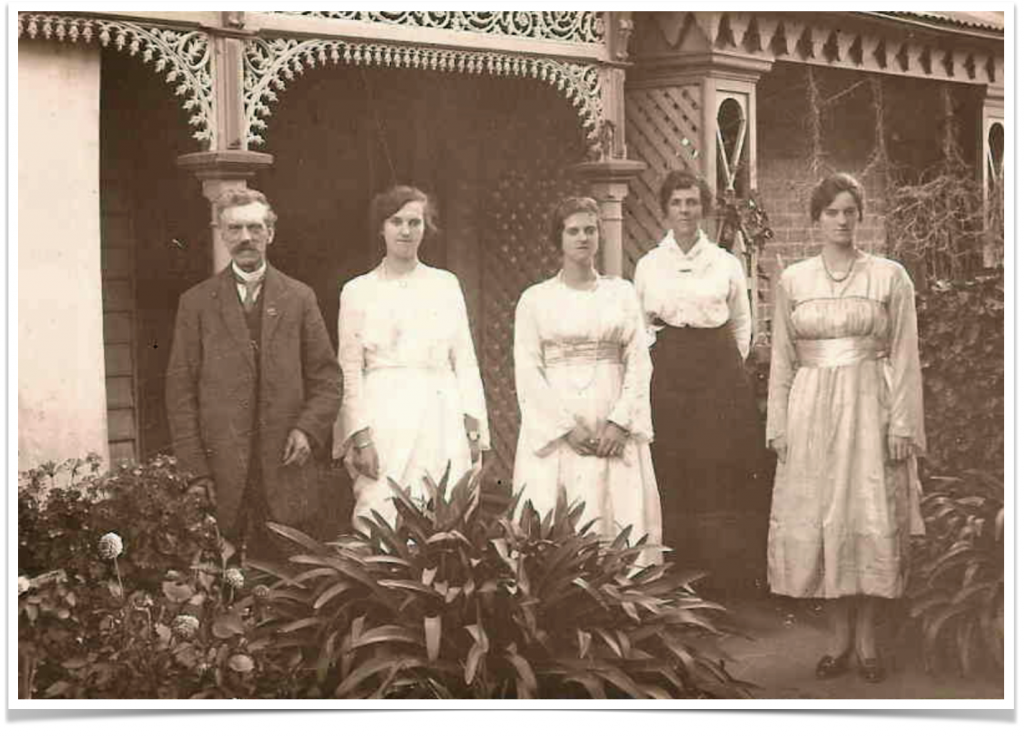

Above: John Malthouse and his wife and daughters outside the home at Dawson Street, Ballarat.

Margaret Ann Malthouse died in Brighton, Victoria in 1930 and John Malthouse followed her on 18th March 1935 at Ballarat at the age of 75.

Of the other Malthouse men of Shildon I have found little else so far, barring a few sad newspaper articles concerning John’s brother George (the one that as a 7 year old had lived away from the family) from around 1910 in the Ballarat Star wherein George makes has a number of brushes with the law on account of several instances of domestic violence against his wife Elizabeth. She tells in court of his bad behaviour and dependency on alcohol. He received a custodial sentence and fines, and in October 1910 she received a decree nisi from him on the grounds of cruelty and drunkenness. I found an earlier article from 1890 concerning a George Malthouse (though I can’t be sure it was the same) in Melbourne where it describes a suicide attempt where he attempted to cut his own throat with a razor after drinking heavily following the death of his wife and a downturn in business fortune. He was tended to in hospital and reported to be expected to survive. Should both stories indeed be reflective of the same person this hints at someone struggling to make good of his chance at life. The evidence is probably out there to enable me to put this latter article into its correct context – i.e. whether the Georges were one and the same – but for now I will return to studying the main subjects of The Wizard and The Typhoon.