As a researcher into Tom Bulch, I’ve been (very gratefully I might add) receiving some help from the Patron of our group, Tom’s grandson, Eric Tomkins. Eric has some very early first-hand memories of his grandfather and started looking into his grandfather’s story long before it came to the attention of this group, and as a family member has insights from conversations with his parents’ generation (Aunts and Uncles too) that would certainly have eluded us.

One of the many questions Eric has helped to try to answer is how it was that a young railway blacksmith of great talent but little means from County Durham managed to open a music shop within a couple of years of arriving in Australia?

We know plenty of Thomas’s early life in Shildon. He was not born into a wealthy family; far from it. The Bulch family, like most families of the day, was a large one with many children sharing the two-up two-down terraced house with father Thomas Bulch senior and his wife Margaret. Though they appear to have been supporters of the Temperance movement and by implication able to save a little money rather than ‘drink it’, they would have had precious little coming in to save.

We don’t know for sure, but there is evidence to suggest that Thomas’s passage to Australia would have been paid for through community fundraising rather than by Thomas or his family. We know that his passage was ‘unassisted’ in that it was not incentivised by the state. There are newspapers reports that confirm that at least one benefit event was held in new Shildon to help to pay for his brother Frank’s passage to Australia. Frank and his wife followed Thomas out around a year after Thomas arrived in Australia, though that became an adventure that was not destined to end well.

Thomas Edward Bulch arrived in Australia on the ship Gulf of Venice mid-way through 1884 with nothing other than whatever he had taken with him for the journey, which we know from what Eric tells us about how he and his friends would entertain the passengers with their rehearsals on deck, included his cornet. After all, what self-respecting musician would leave home without their instrument and supply of their favourite sheet music, some of which would have been his own early T A Haigh published compositions? Surely it would take some time to establish himself in his new world.

And yet before 1885 was concluded he had met and married the woman who would be at his side for the rest of his life, Eliza Ann Paterson. How these two met is a matter lost in time, but Eric suspects that this union may in part be key to Thomas’s subsequent establishment as a businessman in the Ballarat area of Victoria.

Eric had written of Eliza Ann Paterson previously in his splendid “Thomas Edward Bulch: Musician: a family history” (a donated a copy of which is now held at Durham County Library) where he pointed out that Frank Bulch “obtained work in Creswick at the Davies’s Junction Lead gold mine. Thomas’s father in law was the mine manager.”

The person he was referring to was one John Southey Paterson. Eric theorised that perhaps the father of Thomas’s new wife may have wanted to get the young couple off to a good start and so may have been instrumental in setting Thomas up in business. He has looked further into John for us and wrote with the following.

“Some details of John Southey Paterson’s history may be of interest to you following my comment he may have supported Thomas with finance. John and his brother Robert arrived in Melbourne from Montrose, Scotland on the ship Algiers in June 1857. From there I located them in Inglewood in northern Victoria working as miners on the goldfields. They were living in a boarding house in the town. John apparently took a liking to a young servant girl at the boarding house. He married the girl, the wedding was held in the boarding house with the blessing of the proprietor. The marriage was held on 18th December 1861, John was 27 years of age and his wife Sarah Anne Cartner was 17 years of age. Later they moved south to Creswick where Sarah’s father had a small farm. John quickly established himself in the town as an investor and mine manager. He invested in the purchase of two properties with Sarah’s father George Cartner.”

“Sarah’s father was a farmer living in Pontefract Yorkshire before emigrating to Australia with his family. His daughter Sarah Ann Cartner was about 10 years old on arrival in Australia. George’s wife died shortly after arrival in Melbourne on 1 February 1854 age 33 years. It is not known how long the family stayed in Melbourne or when they reached Creswick; nor how Sarah came to Inglewood to work as a servant in the boarding house.”

Eric attached a newspaper article describing gold strikes in Inglewood in 1861 the period when John married Sarah.

He goes on to say, “Some 10 or more major companies were formed in Inglewood each with many stockholders. Whether John invested in one of these companies, employed with one, or searched as a fossicker is not known but he seems to have made money before leaving for Creswick. His sons became farmers as they left home, probably supported by their father to buy properties. I visited one of these farms with my mother when I was about five years old, it was near Creswick. It was about 2000 or more acres, growing wheat, raising sheep and breeding Clydesdale horses.”

Eric attached this photo of the monument in Creswick cemetery on John Southey Paterson’s grave. An additional inscription has been added for his wife Sarah’s father George Cartner on one side of the monument.

It’s certainly a compelling theory and given John’s generous acts in setting his sons up as farmers, there is no reason to believe that he would not have taken some action to ensure some comfort for his daughter by helping her new husband reach his potential in Australia.

I thought we could take a look into what additional evidence of the time tell us about what kind of man John Southey Paterson seems to have been.

He was born in Scotland, the son of Alex Paterson and his wife Elizabeth and spent a childhood in that country before, as Eric explained, his emigration to Australia with his brother.

John seems to have moved his relationship as mine manager from company to company. A notice in the Ballarat Star of 4 Mar 1878 explains that he has just been appointed mine manager for the De Murka Company based in nearby Kingston, having previously been working for the Bunyan’s Company.

In 1881, John was toasted by the Mayor of Creswick at an unusual ceremony to start new machinery at the Davies’ Stonebarn Company at the Spring Hill mines. John was being celebrated in the toast as the engineer responsible for the installation of the new pump and winding engine. Prior to this he may have had connections to the Berry Consols Extended Company in the area as a notice of appointed company officials on 22 Dec in the Ballarat Star appears to suggest that he had left a vacant post which was filled at a meeting on the 21st.

In 1884 John was the mine manager of the Loughlin Mine as a story in the Ballarat Star on 10th May explains that he had given the correspondent from the Creswick Advertiser (whose article was reposted in the Star as well as the Melbourne Argus) a tour of the underground workings of that mine on Weds 7th May. John had explained his plans for the development of the workings. “Mr Paterson states about 1500 feet of ground can be worked north from the incline, and there is about 3000 feet from the present workings to the northern boundary.”

It was in July 1885 that John Southey Paterson was appointed as mine manager of the Davies’ Junction Mining Company, following the resignation of their former manager Mr Jno. Harvey. A report of a meeting of the company in the Ballarat Star of 22 Sep 1885 indicates that soon after his appointment, John discovered the current ‘wash’ to be unproductive and proposed a new direction which was now being worked and which the company hoped might soon reap dividends for the shareholders.

This would, of course if you are now familiar with the overall story we have been revealing on this website, be the drift in which Thomas Edward Bulch’s brother Frank would be killed by a fall of earth in July 1886. Thomas had arranged for Frank to work for his father-in-law John.

In August the same year, legal proceedings were taken against John Southey Paterson as mine manager under the Mines Regulation Act for not having tested a boiler which then collapsed. John’s defence, according to the Ballarat Star was that it had been tested by the previous mine manager prior to him taking charge, and a record book was produced to prove it. He also claimed that the pressure gague and safety valve at the mine did not correwspond so he had ordered a new steam gague which was being tested at the School of Mining when the boiler collapsed. Nonetheless, the conclusion had been that he was guilty and he was fined a substantial £10 with eight guineas legal costs.

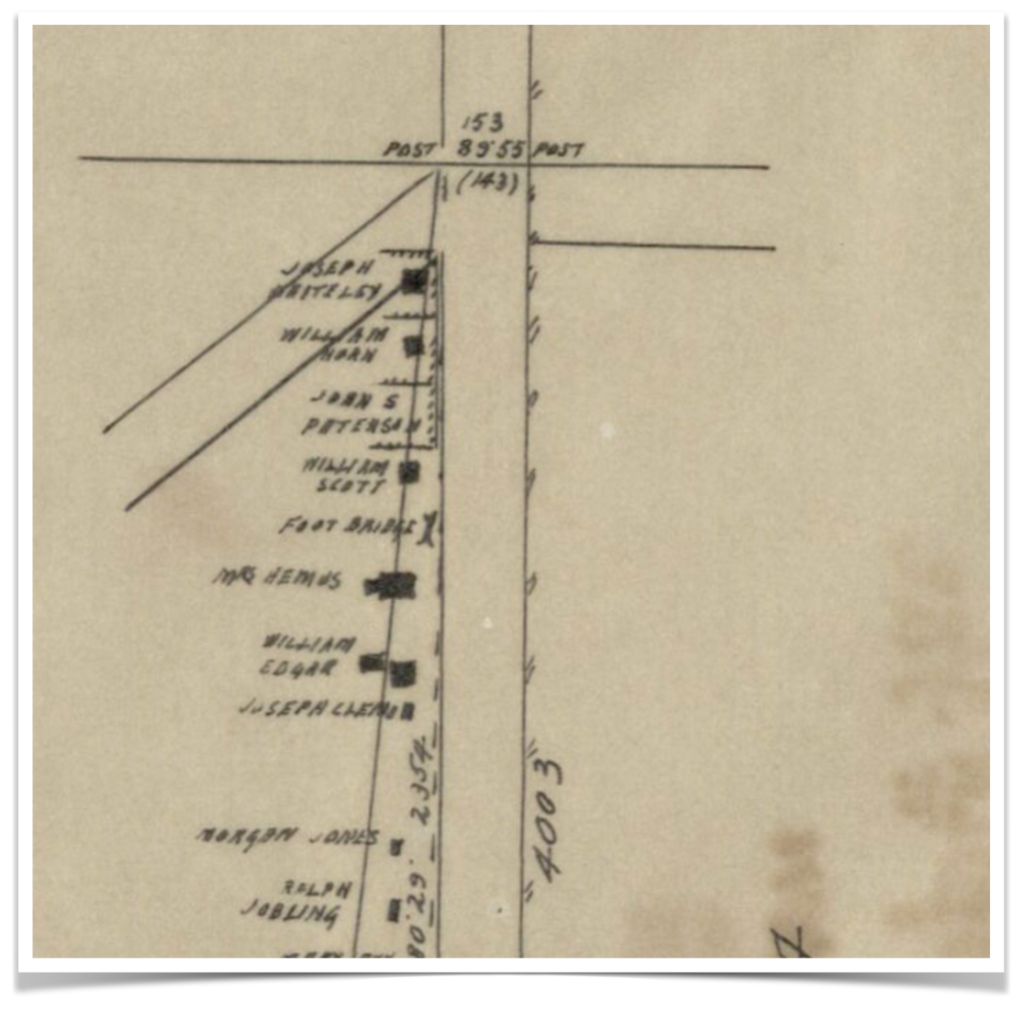

A quick search on the Trove website reveals that in 1887 John was an applicant for a gold mining lease in the Creswick area, which includes a diagram that appears to show a property held by him on a roadside row of what looks to be residences (other occupants are named).

A later report in the Star of a fire suggests that John had a residence on “the Clunes road.” Is that what is represented on this map? That report and another from 1896 reporting storm damage suggest that John kept his Ballarat area properties. This is supported by evidence in Rate Books from the Creswick area.

John’s next move perfectly puts the value of that £10 fine into perspective. It happens in 1888 and is again reported by the Ballarat Star “Mr J S Paterson, late mining manager of the Davies’ Freehold Mine, has just received an appointment as mining manager of one of the Broken Hill companies, at a salary of £10 per week. Mr Paterson, who leaves at once for that field, was selected for that position out of 65 applicants.”

£10, therefore, would have been around a week’s wages, which though today does not sound like much, it would have meant he was quite well off at the time. The Ballarat Star of 30 April 1888 explains how a banquet was held on the 28th in his honour at the Dunn’s Club Hotel where 32 members of the Mining Managers Association attended to honour him as well as “several prominent citizens”. The chairman toasted John and commented on how New South Wales and South Australia were taking away Victoria’s best mining managers. John responded by saying “It was not a pleasant thing cutting old ties and associations, and his mind would always revert with pleasure to his residence at Ballarat.”

In 1889 John Southey Paterson donated some of his possessions to the geological museum in Allendale. The Ballarat Star of 13 Dec 1889 explains. “The local geological museum has again become the recipient of a very valuable collection of ore specimens, kindly sent by Mr John Southey Paterson, mining manager, of Broken Hill, per Mr John English. Mr E J Alexander has received the gift on behalf of the institute.”

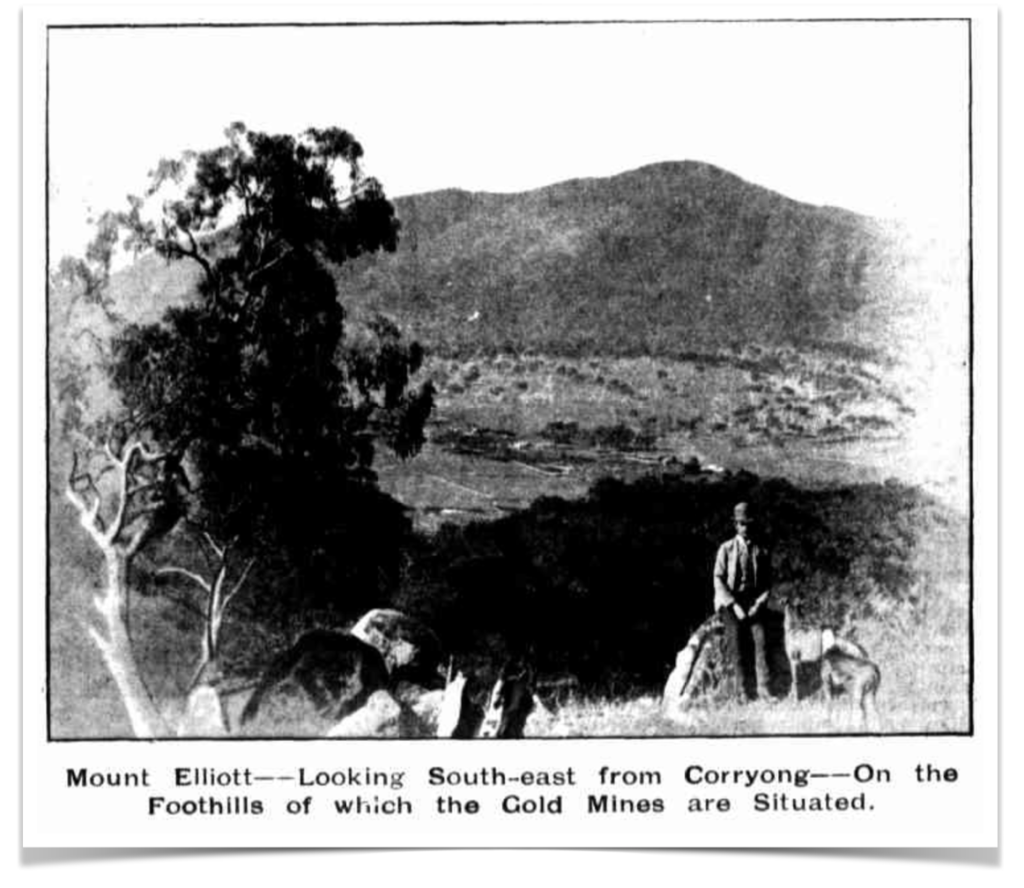

In 1896 John is reported in Table Talk, a Melbourne publication, as being the Mine Manager at the Mount Elliott goldmine, owned by the New York Gold Mining Company. He is reported as explaining the prospects of the mine as in some instances yielding up to 17 ounces of gold per ton mined.

By March 1897 John had moved on to the neighbouring Fenby’s Reward mine which had just been taken over by a new syndicate. The Auustralian Town and Country Journal of Sydney reported this on the 6th March 1897 along with several photographs of the area including this one of Mount Elliott itself.

John passed away in June 1899, after which the following Law Notice appeared in the Ballarat Star of 23rd August 1899 advising any claimants to come forward to ensure they got what they were due from his estate.

“PURSUANT to the “ Trusts Act 1890,” notice is hereby given that all creditors and others having any CLAIMS against the estate of JOHN SOUTHEY PATERSON, late of North Creswick, in the colony of Victoria. Mining Investor, deceased, who died on the nineteenth day of June, one thousand eight hundred and ninety-nine, and probate of whose will was on the twenty-eighth day of July, one thousand eight hundred and ninety-nine, granted by the Supreme Court of the said colony in the probate jurisdiction to the BALLARAT TRUSTEES EXECUTORS & AGENCY COMPANY, Limited, and Sarah Paterson, of North Creswick aforesaid, widow of the said deceased, the executor and executrix appointed by the will, are hereby required to SEND PARTICULARS of such claims to the said executor and executrix, at the office of the said company, situated at Camp street, Ballarat aforesaid, on or before the seventh day of October next, and that after the said last-mentioned day the said executors and executrix will proceed to distribute the assets of the said John Southey Paterson, deceased, amongst the persons entitled thereto, having regard only to the claims of which they shall then have had notice and will not be liable for the assets or any part thereof so distributed to any person of whose claim they shall not then have had notice. Dated this 22nd day of August, one thousand eight hundred and ninety-nine. MITCHELL. NEVETT and ROBINSON Lydiard street, Ballarat, Proctors for the said executor and executrix.”

In his probate records John is cited as having been a Mining Investor, so much more than just a manager of mines. Probate was filed on 26th Jul 1899. The documents explain that he left real estate in the state of Victoria of around £200 in value and £1600 of personal property. His wife Ann survived him by around twenty years, passing away herself on February 13th 1920 to be buried with her husband and father. The grave memorial is a significant one and certainly one you might associate with a wealthy family.