This piece has been inspired by the fact that I have just rendered an arrangement of one of Tom Bulch’s military descriptive fantasias – The Young Recruit – in Sibelius software, a recording from which will be featured in this post. It had me reflecting upon how important the military tradition was within the Bulch family, even though it was not their principal career choice.

The Young Recruit, as a piece of music, describes a day in the life of a young soldier, from the break of day, through waking, getting ready to go on parade, to the parade itself after which the young soldier has time to think of his friends and family and home before a march and triumphant return. It is a piece of music based upon military life in peacetime but stressing the importance of the regimentation of military life. It was written, we think, in around 1894 – predating the Boer War, though there was always a military threat somewhere in the British Empire, or concerns about preparedness for an invasion. Tom was as au-fait with the instrumentation of a military band as he was a brass band and could compose very effectively for both formats.

Before playing the music I thought it would be good to consider the military experiences of Tom Bulch and his father before this particular piece of music was created – and then after listening to the music we can go on to cover some key points from Tom and his sons’ military experiences afterwards.

Even before Tom Bulch was born, in 1862, his father, also called Thomas, despite being a railway employee and locomotive fireman first and foremost, was a part time soldier. The position of locomotive fireman was a much sought after job in those days, and one which he would have had to work up to, through a chain of more menial posts, and in normal circumstances his next career progression would have been to become a locomotive driver. When not engaged in long hot hours of that work, though, Thomas was involved in the 4th Durham Rifle Volunteer Corps, based at nearby Bishop Auckland.

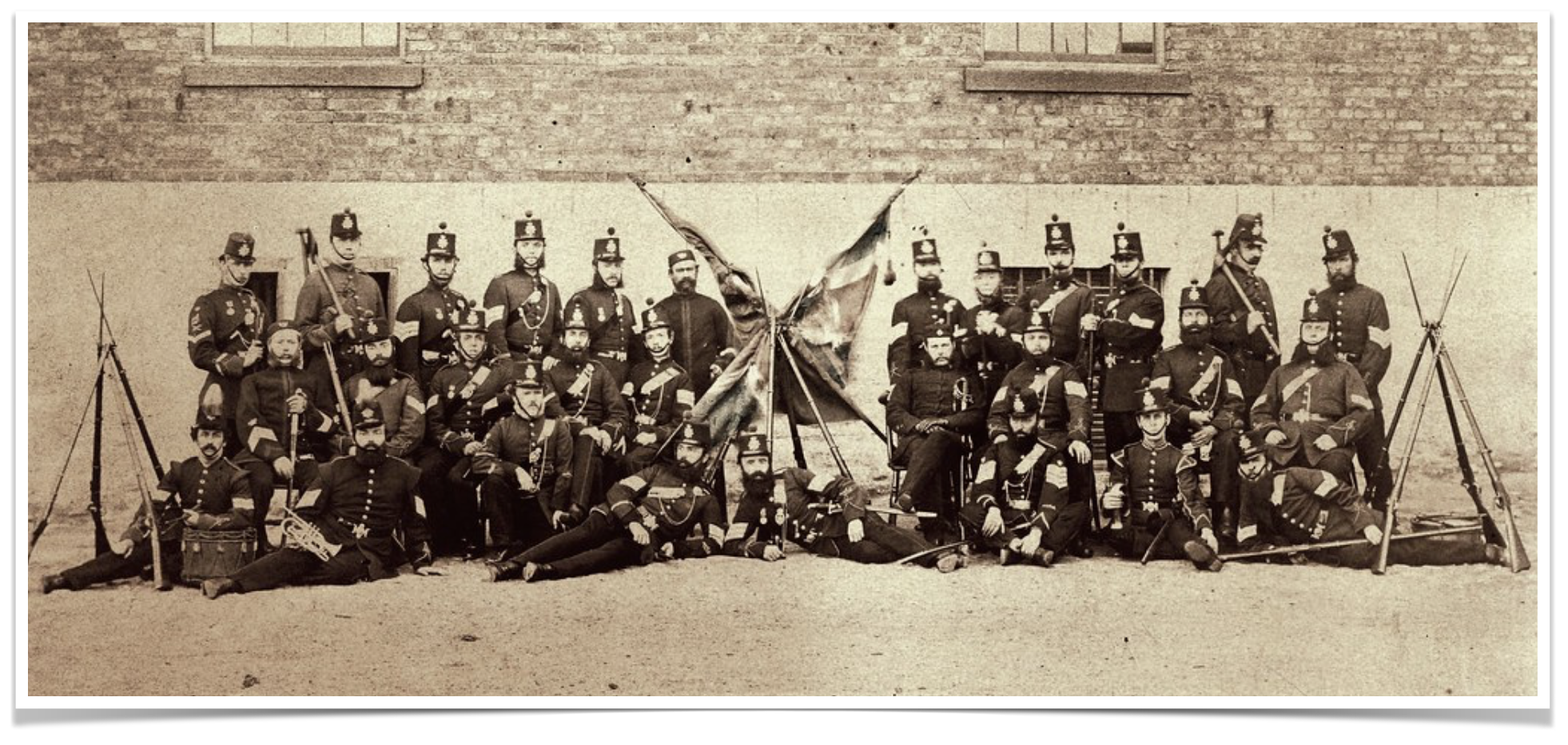

The accompanying image of this blog entry is of an image of a group of NCOs from the 3rd Durham Rifle Volunteers, a similar unit but based in Sunderland.

The 4th Durham Rifle Volunteer Corps was one of a number of volunteer units, rather like a territorial force or ‘home guard’ created to defend Britain in the event of an invasion by a hostile power. This unit was formed in May 1860, following an invasion scare in 1859. A corps had to consist of at least 60 men, and each would be provided with a limited number of Enfield rifles. Any remaining rifles would need to be obtained by the men of the unit themselves. members had to be approved by a corps committee, and as well as most men having to fund their own rifles and uniforms, a subscription of £10 was payable – a substantial amount in those days. It was a largely middle-class movement, and attracted many of the local gentry to become officers. There must have been something about Thomas Bulch that thrived in this setting as he was promoted to Sergeant – probably as high as a man from his background would rise in the unit – and did well in the local shooting contests that were held to encourage the men to work on their accuracy. We have seen one report from as late as 1871 where Thomas took part in the Helmington Challenge Cup shooting competition, with a prize having been offered by Mrs Spencer of Helmington Hall.

By that time, young Tom Bulch would have been around ten years old, and probably quite used to seeing his father in his 4th Rifle Volunteers uniform and acquired some appreciation of the military tradition. His father must have been something of a disciplinarian to have become a non-commissioned officer and have men take his orders. This might well have been one of the contributory factors that led to Thomas senior being made a Timekeeper at the railway works after the serious life threatening accident of 1861 in which he was thrown from a derailed locomotive and trapped, scalded, under it for hours on the bleak moors between Bowed and Stainmore. He was probably made from some stern stuff.

Young Tom might well have aspired to be a bit like his father. His decision to follow the Temperance path and take charge of the Temperance Band in new Shildon rather than remain with his Grandfather’s Saxhorn Band, of whom there were well reported disciplinary incidents on occasion. When Tom emigrated to Australia it’s unsurprising that he later tried to form another Temperance Band in that model. First though he had to make his name with bands that were already going. As well as receiving the reins of the Kingston and Allendale Brass Band from his old friend John Malthouse, Tom enlisted in the 3rd Battalion Militia in Ballarat to become their bandmaster. It’s quite possible that he used some of what he had learned from his father to prove his suitability for the role – though it would have been his musical prowess, rather than his military prowess, that saw him elevated to his post as an NCO and bandmaster with that unit.

He did well, and newspaper reports of his efforts in working with that band were very favourable, though his tenure of the 3rd Battalion Militia was only a few years in duration. The ending of that tenure came about through an incident at the end of 1886 wherein the officers of the Battalion failed to live up to Tom’s exacting expectations with a particular flashpoint occurring when a platform for the band to perform upon had not been erected for a concert. Tom decided that his values and standards were not compatible with the way the 3rd Battalion Militia operated, and duly resigned.

His next move was to try to return to a model of band he was more comfortable with, and over which he could exert his total influence. He attempted to set up another Temperance Brass Band in Ballarat – which quickly ditched the ‘Temperance’ label to become Bulch’s Model Brass Band (no doubts as to who was in charge there) – and eventually, when he left Ballarat, became the Ballarat City Brass Band which still goes strong today.

Tom wasn’t finished with the military band format – later becoming bandmaster of the Melbourne GPO Military Band.

As we said , The Young Recruit was created, we believe, in about leat 1893 or early 1894, a period when Tom lived in Melbourne and was engaged with both the GPO band and also his own Prahran Operatic band. Between that year and his death in 1930, we have found at least 146 instances of it having been reported as being played by different bands – suggesting it was one of his most popular works ever. Of course it would have been played far more times than was reported in the press. The very first band reported as playing it, though, was his old friend, and former Shildonian, Sam Lewin’s Bathurst District Band who played it in Machattie Park, Bathurst on the 5th February 1894.

Take a moment or two, then to hear what that audience in the park would have heard that day – and see how it makes you feel. As I said before, it starts with the break of day…

…and with that grand ending we move on. Tom’s involvement with the Military music format didn’t end there. He made a return to the 3rd Battalion Militia in 1900, during the Boer War, again as bandmaster. He resigned in 1903.

He also created another military descriptive fantasia – The Bombardment of Port Arthur – in 1904 inspired by an event in the war between Russia and Japan. We gather, from a news article, that the Japanese adopted this piece and that their military bands played it. We’ll explore piece that another time.

From here, it was the turn of his sons, Thomas Edward Bulch Junior and John Southey Paterson Bulch to take up the military tradition – though this move was heavily influenced by the outbreak of the First World War.

Tom’s two sons had both been bandsmen as young lads and then young men, playing a part in their father’s bands, with Thomas junior particularly doing well and becoming a solo cornet player.

It was Thomas junior that was first to enlist after the outbreak of the war, and of course he was assigned to his battalion’s band. Military bands had an important part to play in the British Empire’s military stricture and operations. The music accompanied end enabled structure both on parade an on the battlefield, with particular tunes being used to communicate particular battlefield moves. By the Great War it was more a matter of parades and morale boosting – with passionate and rousing march music being used to stir the soul and when necessary soothe the men away from the front. But the men of the military bands that saw action in that war were every bit as much soldiers as the rest – seeing front line action.

Young Sergeant Thomas Edward Bulch, promoted to that rank in the field, and his bandmates in the 23rd Battalion Australian Imperial Force saw front line action at Gallipoli before moving on to France. They were not always accompanied by their instruments, though the military logisticians usually eventually made sure that they were reunited from time to time, and supplied with new sheet music – some of which was created by Tom Bulch back in Australia. These included many military themed marches based on WWI events such as “General Joffre” and “Heroes of Gallipoli.”

Tragically, Sgt Bulch didn’t return from France. He was killed by shrapnel when his unit was shelled heavily on June 19th 1916.

Younger brother, John, known to everyone as ‘Jack’ also enlisted soon after that – being assigned to the band of the 23rd Battalion in October 1916 – he also went to France with his comrades, but was fortunate enough to return.

Perhaps inspired by the loss of his son, Tom Bulch also made a return to the army – lying about his age in order to be accepted. Tom was made bandmaster of the Langwarrin Army Camp outside of Melbourne and his third period of service did not see out the duration of the war. Perhaps his true age was discovered

Overall, the Great War, and the tragedies that accompanied it, changed attitudes toward war across the globe, and in some ways attitudes to music. The tunes that promoted the glories of the military life faded into the shadows a little as a war weary world sought something else. The battlefield based conflicts of a bygone era in which men faced each other in regimented rows in a stand-off of honour had been replaced by drawn out campaigns that involved unspeakable horrors of a new age of escalating creativity culminating in a, then unrivalled, massive destructive capability. Whole landscapes lay churned by shellfire. The scars of craters created by huge underground explosions are still visible across Europe. The world hoped that that particular experience had been a “war to end all wars” and that such times would never return. In a way, the growing aversion for that military tradition contributed to a dip in the interest in works by Tom’s Bulch’s generation of composers.

Looking back though, it’s a fascinating period to reflect upon. When you see the old sepia photographs of the volunteer solders of Tom Bulch’s father’s generation looking dashing in their bold and bright uniforms – designed unlike later battle dress so that they might be easily seen and distinguished on the battlefield – almost like how a sports strip identifies teams on the football pitch. You can see how important the availability of proud military music was to declare that being a regular or volunteer soldier was an honourable thing to be. It would also have been important to make people want to fulfil this important role, and join the defence forces across the Empire. Music like The Young Recruit was as much a recruiting and propaganda tool. What young man could have sat listening to it’s rousing emotive and triumphant melodies in the evening sunshine and safety of an Australian park without thinking that they should already have joined their kinsmen in defence of their country. What young lady would not hear it and be proud that her absent sweetheart was away serving and protecting her family from aggressors.

Yes – the psychology of music is a fascinating thing.