It’s hard to believe that the last time that we heard anything new in person from our collection of George Allan and Tom Bulch music was back in August 2018 when we had our first concert at Ushaw College. A second concert we had planned, in partnership, was to have happened in April this year at Locomotion, the National Railway Museum at Shildon, and then of course the Covid-19 pandemic hapened – resulting in the main organisers cancelling that show as well as our project with the children of Greenfield Academy.

Getting a little time from a brass band while there isn’t a virus pandemic is quite tricky. First of all most of the banding community seems to be constantly focused on preparing for their next contest – which you can understand as that doesn’t seem to have changed since George and Tom’s day. Secondly, modern life is busy and for bandmasters to schedule a date where all of the band is available to play isn’t easy either. Thirdly running a band doesn’t come for free – so a fee needs to be agreed, and when you compare what pubs and clubs pay for a three or four piece band with what you might pay for a brass band then, actually, a brass band is remarkably good value though conversely barring the top bands that command high fees, it offers little incentive for the band. Naturally, of course, when the virus reared its tiny and unpleasant head, it was all over for the banding community – for the time being at least.

This raised the question for us as to how on earth we might explore some of the music we hold if we’re not going to get a band to play it?

“Well,” I thought, “it’s not all band music – Tom Bulch created a lot of piano music to sell too – how about we start with some of that?”

The first thought was to seek out a pianist to explore some of that. Now, I know a few people who can play piano, but not fluently, and I really wanted to see how the music sounded when played well. Luckily I know the owner of a music shop locally. I call him Mr Tim, and he has a wide network of contacts. So I got in touch to see who he might recommend. I have to confess to being slightly surprised at his answer.

I have always been of the mindset that if you can use a musician, you should; though I know there has long been more than one way to ‘skin a cat’ as the expression goes. Mr Tim, however, suggested that I fall back to using some professional music software – Sibelius.

I knew about Sibelius, of course, as Steve Robson – our MD – uses it to create score for his own compositions and projects. He’s also tremendously busy so I hadn’t anticipated ever asking him to try this. So, wanting to make some progress I figured I would give it a go and purchased, downloaded and installed the software. Though I do play a range of instruments, and have done since junior school, I certainly wouldn’t consider myself a musician in the same sense as Steve and Kelly from the group are – and I’m not a fluent reader – however the software was surprisingly intuitive as long as you understand the rudiments of music notation.

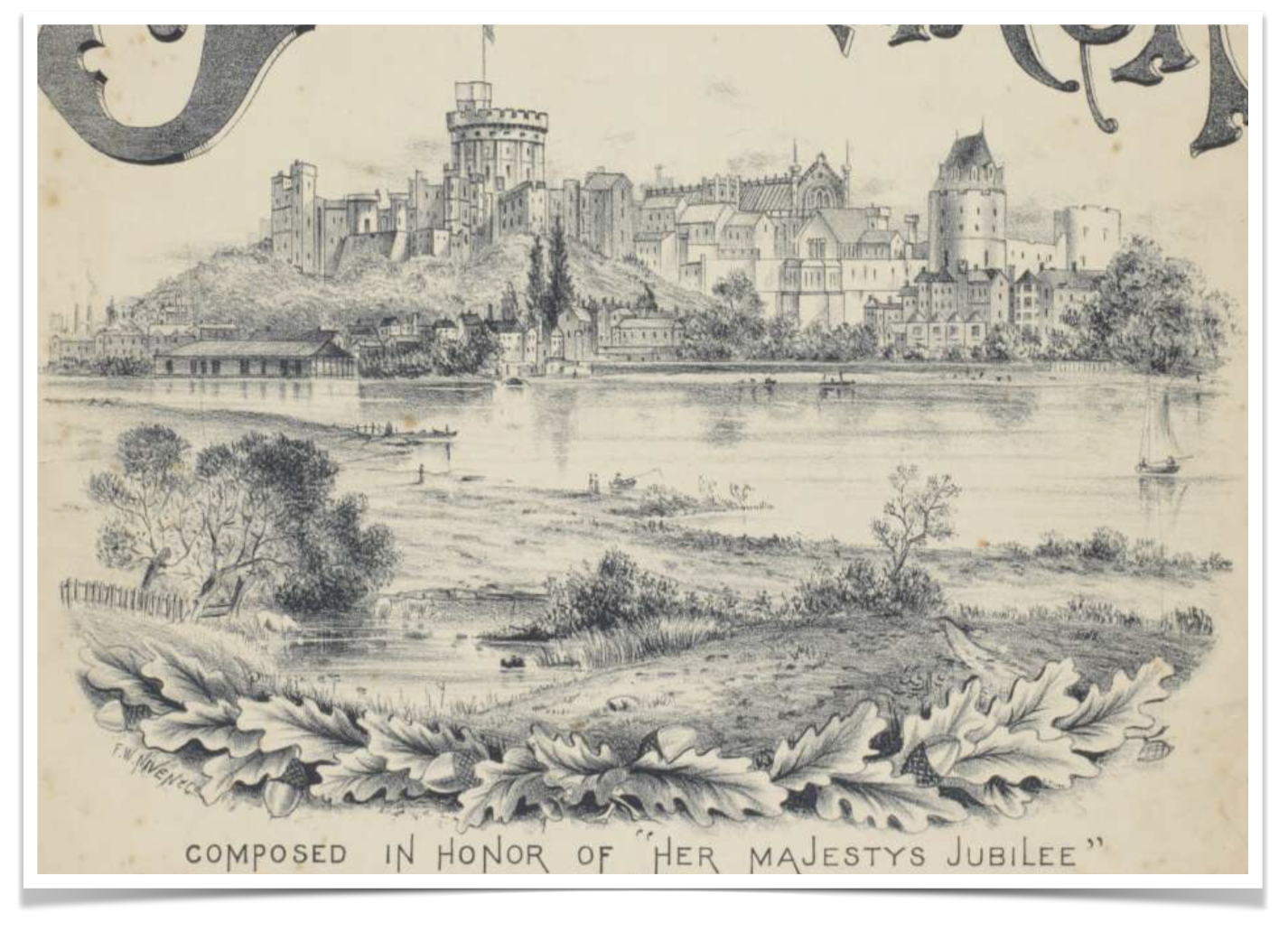

I chose to start with Tom Bulch’s “The Jubilee March” – a piece he created in Ballarat for the Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887. He created it for the mass market, in that it was expected to be a piece that anyone with reasonable skill could buy and play at home but it wasn’t expected to be demanding or to impress the listener other than being a lovely and appropriately regal sounding march tribute to the monarch. Tom wanted to sell lots of copies of the music – and given that the Jubilee would only happen once it was a piece that would have relatively limited relevance. (George did similarly when he created his King Edward overture for brass band, with the new monarch’s coronation in mind – and probably learned that same lesson)

The front cover of the sheet music features a printed reproduction of what looks like a superb detailed sketch of Windsor Castle from across the Thames, with a bed of oak leaves in the foreground – a scene that has changed surprisingly little between then and now.

In all, on account of getting used to the software, it took me an afternoon and part of a morning to transfer all of the notes from the paper to the digital score on screen – though of course I could pause from time to time to listen to what had been entered so far. It sounded surprisingly good, and I was surprised at how well the software managed the dynamics etc. I probably shouldn’t have been, to be fair, but you know when you start to hear something come together that you weren’t sure you were ever going to get to hear. At that point I might even have been grateful to hear it twanged on a shoebox harp made with elastic bands.

From just a few hours of concentration and information transfer, I was suddenly transported in my imagination back to 1887 and Tom Bulch’s home in Ballarat sat in the dim glow of the lamplight with his wife Eliza as we both listened to him demonstrate the march with his handwritten manuscript before him on the simple upright piano. I was hearing for the first time this echo of a moment in history. I wondered how many years it had been since anyone sat before a piano to run through the piece for pleasure, and felt a little sad that to make this happen I had had to enlist the assistance of a machine.

My thoughts on the piece – well, I do think it had a regal and ceremonious feel to it, and despite the bold march accents there is something delicate and feminine about the accompanying melody. It certainly conjures up images in the mind of royalty and the sensibilities of the era throughout its movements. I found it pleasing – but then I probably always would as I’m an enthusiast on the subject matter.

I’m not to feel too bad about it though, as it means that I now have a version of it that I can share with you all through this site. I have added it to this page so you can all have your own 1887 moment. In the meantime, flushed with reasonable success I resolved to try a piece of band music – and I’ll share the outcome of that with you in my next post.