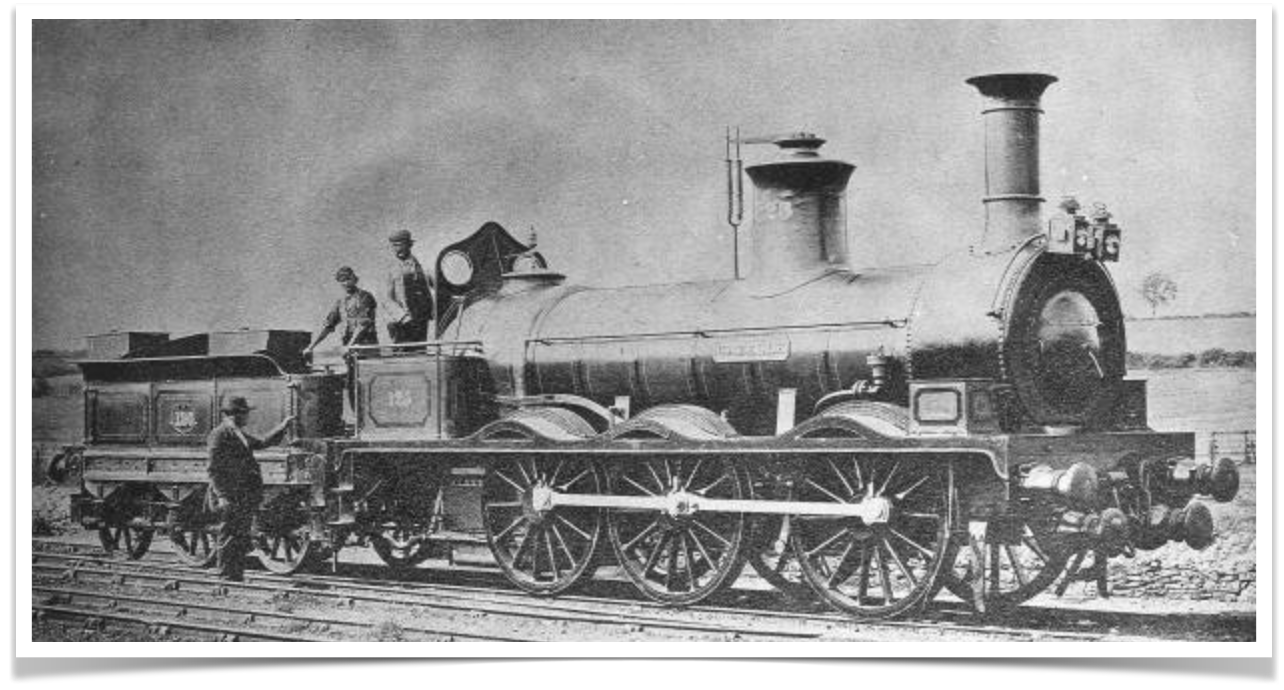

This week I am still reeling from the discovery of a story of a day that could have changed everything, and may well have meant that I would not be creating this website here in 2018. The day I refer to being the day that a locomotive rather like this one illustrated above (No. 125 “Gazelle”) derailed and almost crushed, burned and scalded Thomas Edward Bulch’s yet-to-be father to death.

It was 1861 (the year before Thomas Edward Bulch was conceived, and born) and the Stockton and Darlington Railway had recently celebrated a new partnership, and the opening of a new line. The South Durham and Lancashire Railway had been created by the S&DR to connect Bishop Auckland in County Durham with Tebay, enabling onward travel to the Lake District and Cumbrian towns. Work commenced in 1858 on this route heading south-west from Bishop Auckland through Barnard Castle and Bowes then, taking a detour around the Duke of Cumberland’s holdings, over the moorland into Cumbria via Stainmore crossing four newly built viaducts along the way, at Tees Valley, Deepdale, Belah and Smardale Gill.

Interestingly, Thomas Edward Bulch’s grandfather Francis Dinsdale’s New Shildon Saxhorn Band had entertained at the celebrations following opening of the 161 feet high iron lattice Deepdale viaduct in December 1858 at the Railway Hotel (now the Old Well) in Barnard Castle.

You can still see the embankments and cuttings of the route the line followed if you visually trace the landscape westward from Bowes, or north from Barnard Castle, using Google Earth. This is a landscape which, unlike our towns that have since been extensively remodelled, would have changed relatively little since the year of the crash. Parts of the route are now preserved as public walkways, though there has been an attempt at Stainmore to revive a stretch of the railway in a pre-Beeching 1950s style.

Up until 1861 the Stockton & Darlington Railway has been primarily about the movement of minerals and goods, but there was an increasing demand for passenger services, and locomotives suitable to haul them. Two new 4-4-0 locomotives were commissioned to operate on this line; “Brougham” and “Lowther”. They were designed by William Bouch (who had been an apprentice of Timothy Hackworth at Shildon, and risen to become the Chief Superintendent of the Stockton and Darlington Railway) and built by Robert Stephenson’s locomotive works. However, despite the introduction of the new 4-4-0 locomotives, a number of 0-6-0 mineral locomotives like “Gazelle” were also used for leading passenger trains. The locomotive involved in this incident was later identified by the investigator, Captain Tyler, as No. 1491, which had been built in April 1860. Regrettably I’ve not found a photograph of that particular locomotive.

Though the route had been followed by mineral trains since July of that year, there was a formal opening ceremony of the South Durham and Lancashire Railway held on 7th August 1861, and passenger traffic commenced, promptly, the following day.

The route was famed for its harsh and inhospitable weather, and the locomotive crews, over time, revelled in their resulting reputation as being ‘hard men’ for bearing it with little but a turned up collar and an open cap to protect them from the wind, sleet, snow and rain.

The incident in question, though, occurred three weeks after the opening, on Thursday 29th August. It was reported, most ably, in the Durham Chronicle on Friday the 6th September. I am unable to improve upon this eyewitness account so I will insert the extract here as it was printed.

“ALARMING ACCIDENT ON THE SOUTH DURHAM AND LANCASHIRE RAILWAY – On Thursday week, about half-past seven o’clock in the evening, an accident occurred on the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway, which, it will be remembered, was opened on the 7th ult. It appears that an excursion train, under the auspices of the Darlington Mechanics’ Institute, had been at Windermere, and were returning. A correspondent furnishes the following account of the accident –

The first pleasure trip to the lakes was taken on Thursday, the 29th ult., over the new line from Barnard Castle to Tebay, and accommodated about 400 excursionists from Darlington and Barnard Castle. The train steadily driven to its destination at Windermere, the journey was fully enjoyed, the weather being delicious throughout, and the scenery beyond Winston an uninterrupted succession of ever-changing beauty. Amid Wordsworth’s favourite haunts the party spent eight merry hours, rambling over mountains and glens, gathering ferns, and listening to the echo of “the post horn.” No happier day till 5:30 p.m., when the train started punctually from Windermere, was ever passed.

During the return journey, especially on this side of Kirkby Stephen, many of the passengers, and among them Mr. Geo. Brown. the secretary of the new line, observed a recklessness of pace; the gradients being somewhat hazardous, the way perhaps not consolidated, and the curves extreme, excited general alarm. All at once, close by a cattle creep or bridge, near Low Spittal, three miles west of Bowes, the engine got off the line, and ploughing down the embankment, jerking, shuddering, so to say, bounded into a peaty field, there stuck fast flat on her side.

This happened in a shorter time than it takes to write it. The hour, 7:45 p.m., was closing on the lovely day, with thick gathering clouds and hurrying darkness. There was but one first class carriage which, and another covered, with the last van, maintained their position. The five others were pitched athwart, in odd directions, and many of them smashed, but the coupling chains kept entire. After the first pause in excitement, in which men live their lives again, all that could escape bolted through windows, the doors being locked.

One man, Mr. Fortune, states that before he came to his senses he was spanbowed through the window, such the violence of the concussion. The others, stupefied in heaps, or stunned dotted here and there, were hauled out, some with superhuman effort and incredible difficulty; some were silent, others tumultuous, and the scene altogether beggars descriptiuon. Had this untoward affair occurred a few yards on either side of its point, by nothing but a miracle could a single individual have escaped. As it was, taking into account the terrible shaking and horrible alarm, all suffered; for many feeling themselves wonderfully right on Friday, had to call in advice and keep prudently quiet afterwards. Mr Foggett, of the High Row, was found with his collar bone fractured; Mr. Ridley, whitesmith, a similar catastrophe, and internal injuries; Mr. Michael Watson, builder, who bled profusely, had his head cut; Mr. Fortune, his wrist and chest injured; Mr. Railton, his wrist dislocated; Mr. Dunning, shoemaker; Mr. Dunning, of the George Inn; Mr. Harrison, silversmith; Mr. Spence, seedsman; Mr. Lee, bookseller; Mr. Maitland, Mrs Wallis, Mrs Edmondson; Mrs Crabtree, and Mrs Wray, all of Darlington; Mr and Mrs Smith, and Mr and Mrs Moore, all of Cockerton; and old people; were hurt, some seriously. Many had black eyes, others were cut in various parts; one his teeth knocked down his throat, and some suffer internally. But these were trifling, though bad enough.

Dr Torbock, the only surgeon present, and prepared with all the means and appliances necessary, attended to his unexpected patients at once. To the horror of everyone, it was also discovered that the engineman and stoker were actually buried under the engine; their position seemed hopeless, such was the nature of the ground; the awful weight and ponderous mass above them struck every one with the idea that any attempt to extricate them, without the aid of mechanical contrivances, would be futile. The wounded cared for, to the praise of a few – only a few alas – for many there were who refused to help, skulking away unconcerned, a prey, it is to be hoped, to their own remorse – the utmost energy was directed to those poor fellows.

The gloom of the blackest night, intensified by a furious howling wind and pelting rain, which Stainmore knows well to show, added to the baffling difficulties of every one. Fence rails torn up, splinters of carriages gathered together mixed with hay from a neigbouring stack, soon made a prodigious crackling blaze, and the sparks darted along with the angry wind, a distance between the High Row and the church gates. Under the fire, cinders raked from the coal-box fell upon the victims, and any attempt to slake it only added to the horror of the steam which scalded, and the styth which affected them. What a scene this for Salvator or Van Schnendel, or our own wondrous Turner!

If there was leverage enough the weight could be easily raised, but the difficulty was a fulcrum. Big plates were brought from the line, and hard work it was; for in uncertain light and intense darkness, boggy holes lay treacherously in the way; but good hearts never give in. Plank after plank, and stone after stone, sank down, and then at length the engine was moved; but only unfortunately to increase the poor men’s pain, and add fresh anguish to their hopeful friends. Struggling thus till 11:30 p.m. – what a time it was! – the night seemed like three.

By some unaccountable blundering with the telegraph at Bowes, whence stupid, selfish, contradictory messages went home, the lateness of the hour, and the awkwardness of a single line, it was not until the opportune time help came from Darlington, when exhaustion seemed almost to have worked its inexorable will. From that time nothing was wanting – the chief secretary, with heads of various departments, and their workmen, took the matter in hand. The fireman, Bulsh, whose case is the far more serious of the two, was rescued before the brave excursionists departed. Aron, the other man, buried for 8 hours, was not got out till after 3 a.m. Both were taken to their homes at Shildon; and each lies very ill – burnt, and scalded, and crushed. The special trip came cautiously back – arriving at Darlington between one and two; the excitement being intense.

This is the first great accident that ever happened on any line under the direction of the oldest and best managed railway company in the kingdom; and it is to be hoped the fullest investigation into its cause will be made. Contradictory assertions have been confidently bruited about by interested parties. On the one hand, the pace at which the train was driven is considered the sole cause; on the other, the condition of the way, and the weak girders of the cattle creep, “where the engine always jumps;” but all agreed that, had it happened elsewhere, every one would have been smashed; and the extraordinary escape of so many, as it is, is due in a great measure to the soundness and excellence of the carriages. Thus ended a day full of hope, and more than half full of pleasure, to the committee of the institution and their friends – some of whom, loitering behind in Westmoreland, were no little astonished on their return next morning, in passing the end of the disaster, where the line had been remade, to discover the awful danger they had escaped.”

(above: location of the derailment incident 3 miles west of Bowes near Spital Grange)

The Yorkshire Gazette of 7th September adds:

“With the enginemen things had not fared so well, and they were found jammed under the engine in such a manner as to prevent the possibility of extricating them without sending to Darlington for a crane; and as this was the work of several hours, the poor fellows were compelled to endure great suftering. Intelligence of the catastrophe was immediately telegraphed to Barnard Castle and Darlington, and a special train came on to take away the passengers. An efficient staff of workmen commenced operations, and, after a lapse of seven or eight hours, the engineman and stoker were released. The former was severely scalded and otherwise hurt, but it is thought not dangerously. Tho fireman’s was found to be the worst case, for he was scalded all oyer his side and had his leg broken. The van and carriage next the engine were smashed, and it is the greatest wonder how the passengers in them escaped.”

On the 13th September, the Newcastle Journal published an update, thus:

“South Durham Railway Accident – The engineman who received serious injury in this accident died on Sunday afternoon; his name was Robert Aaron and he was 35 years of age. The stoker, Thomas Bulch, is dying; Dr Torbock, who has been in daily attendance on the poor fellow, holds out no hopes.”

The official Board of Trade report of 14th September written by Captain Tyler read in part:

“The driver and fireman were found under a heap of coke, which had fallen on them from the tender, with their legs jammed in between the quadrant of the reversing lever and a cover provided on the engine to shelter them from the weather. They could not be extricated from their position for eight hours, and were so much injured and burnt, that the driver has since died, and the fireman is not expected to recover. A third person, also a fireman in the service of the Company, was thrown off to the right on the grass, and stunned; but he escaped without serious injury.”

The article can be read in full HERE

The Newcastle Journal of 20th September describes some of the inquest proceedings:

“THE ACCIDENT ON THE SOUTH DURHAM RAILWAY—CAPTAIN TYLER’S REPORT. The adjourned inquest the body of Robert Aaron, who died on Sunday the 8th instant, in consequence of injuries received in this accident, was held at Shildon, on Tuesday, before Mr. Trotter, coroner. Deceased, who was the driver of the engine, was found buried beneath the coke, and his legs were held fast by the engine, which was thrown its broadside. Captain Tyler (from the Board of Trade), who came down from. London to inspect the scene of the accident, stated before the coroner his opinion as to the cause of the accident. He said the original construction of the line at this particular point was defective. He had learned that the inspector of the permanent way had ordered the repair of the defect on the day previous to the accident. The plate layers, however, had mistaken the instructions given them, and, instead of making the way more safe, increased the play in some longitudinal beams which span the cattle creep at the spot. Those beams were not fastened in the girders of the bridge, and did not fit in them accurately, and there was some degree of shake in the girders, owing to their not having been perfectly buried in the masonry of the abutments of the bridge, and owing to the masonry having settled, to some extent, since the construction of the bridge. The reason why so little injury was done to the passengers, and why the carriages were so little damaged, considering the serious nature the accident, was partly because the carriages were of considerable length, strongly built, and stiffened with timber placed vertically at the ends. But the principal reason was because very powerful brakes, of Mr. Newell’s pattern, were employed the tail of the train but for which there would probably have been good many passengers killed. The Jury arrived the conclusion that the deceased came to his death by the engine accidentally running off the line ; but what caused the engine to run off they could not say. The Coroner expressed his surprise at the verdict, whereupon A Juryman said there had been various causes stated, and they could agree none of them. The Coroner requested them reconsider their verdict. The Jury again retired, and after the lapse of a quarter of hour returned similar verdict, stating, that how the engine came to run off the line there was no evidence to satisfy them.”

Then as part of a piece in the York Gazette of 28 Sep 1861 the following extract makes acknowledgement to the fact that Thomas Bulch Senior appeared to be pulling through after his injuries:

“The wounded taken care of to the praise of a few — only a few, alas! — for many there were who walked away unconcerned — the utmost energy was directed to those poor fellows, (the deceased engineman Aaron and the stoker Bulsh, who is recovering.) The country people seemed more than half savage. The gloom of the blackest night, intensified by a furious wind and the most sweeping rain added to the difficulty of every one. No help, by some unaccountable ignorance of the telegraph, reached the spot from head quarters for a long painful interval, and the men remained buried for eight hours, when they were brought home to Shildon.”

So, despite the broken leg, the scalding and burning and eight hours spent crushed beneath the locomotive, Thomas Bulch lived. We know from his employment records that we discovered at the National Archived in Kew that the very next year, on March 10th 1862, he changed his occupation to be ‘timekeeper’ at the railway wagon works in Shildon. When I first saw this I confess to having found it a curious change in occupation. The timekeeper’s post was not especially well paid. However given the injuries sustained in the accident, and the probable mental trauma, it’s now really quite understandable that Thomas Bulch may have been unable to continue to crew locomotives.

As we also now know, around 9 months after his change in occupation, and sixteen months after the accident, Thomas Edward Bulch was born, without whom we’d not be telling this tale. The 29th August 1861 was a moment that could have changed everything.