I came across this little march back in about 2019 on a trip to the British Library where a copy of it is held in the reference library along with another three pieces published in what appears to be a fairly rare band journal called the “Standard Band Journal”.

This is a journal of which I’ve been able to find out little at all. Two of the four pieces by George that were published in its pages are from around 1901/1902 and as I’ve been able to find barely a mention of the journal aside from these pieces there is a suggestion that it was short lived. It was published from Boston in Lincolnshire, the area of the country from which Thomas Albert Haigh published his “Amateur Brass and Military Band Journal” and thus may have been an attempt to carry on Haigh’s legacy after he died. I initially thought that it may have been connected to the Boston Standard newspaper, as it was published by the Standard Publishing Company but I’ve not been able to establish a firm link. Besides, the newspaper, though it was published from Boston, seems to have started out as the Lincolnshire Standard and I’ve not been able to establish firm dates when it commenced. There were other ‘Standard Publishing Companies’ elsewhere in Britain, though the band journal explicitly has the place Boston printed on its headers.

The piece has “St. P. Co. 28” printed at the bottom which suggests it was the 28th piece of band music they published. “On Parade” another of George’s pieced they published had “11” suggesting it to be an earlier piece.

The name Niobe seems to have its origins in Greek mythology of the ancient world. She was a daughter of Tantalus, ruler of a city near Manisa in Turkey. Her husband was Amphion, son of Zeus. Her story runs that she was punished by Leto for , who sent Apollo and Artemis to slay all of her fourteen children, after which they lay unburied for nine days while she abstained from food. Then the gods buried them after which she retreated to Sipylus where she turned to stone. A statue exists of Niobe and her children which was displayed in the Villa Medicis in Rome before being removed from there to his gallery in Florence by the Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1770. A painting of Niobe shielding her children was painted by Jacques-Louis David, and there are several other art works depicting the story.

Evidence suggests that George would often name his marches after ships. Most of the other references I have found to Niobe relate to works of art depicting the mythological scene of Niobe protecting her children, but the ship feels instinctively to be the most likely inspiration – but which one? So let’s explore the ships with that name.

There were at least four Royal Navy ships that bore the name Niobe. The first was captured by the Royal Navy from France in 1800. Originally it was called Diane, but the Royal Navy renamed her to Niobe. She was broken up in 1816. A second was launched in 1849, then sold to the Prussian Navy in 1862. The third, launched in 1866, and was a wood screw sloop launched in 1866, four years after George was born, but wrecked in 1874; well before George created this march. The more likely HMS Niobe of inspiration therefore would be the HMS Niobe that was launched in 1897, only a couple of years before George would have penned the march.

Though we cannot be entirely certain of the ship theme to George’s works it’s often quite striking how investigations into this possibility reveals patterns. For example an article in the Glamorgan Gazette of 1st January 1897 giving an update on progress in the manufacture of Royal Navy ships mentions that the hollow crank and shafting for Niobe had been completed, and mentions 11 other ships including Jupiter and Europa, which by possible coincidence are also names of George Allan marches. A note of caution comes in though when you consider that the West Hartlepool Theatre Royal was advertising in The Era the next day that it was taking bookings for, among other things, “Niobe” – presumably a play. Also we have to point out that there was a commercial ship named Niobe that also in January 1897 was making its way from San Francisco to Ipswich, Australia. Shipping movements were frequently reported in many of the newspapers George would have access to at the Shildon Railway Institute reading room, but it was progress on the Royal Navy ship, and subsequently its military missions, that dominated the newspaper coverage.

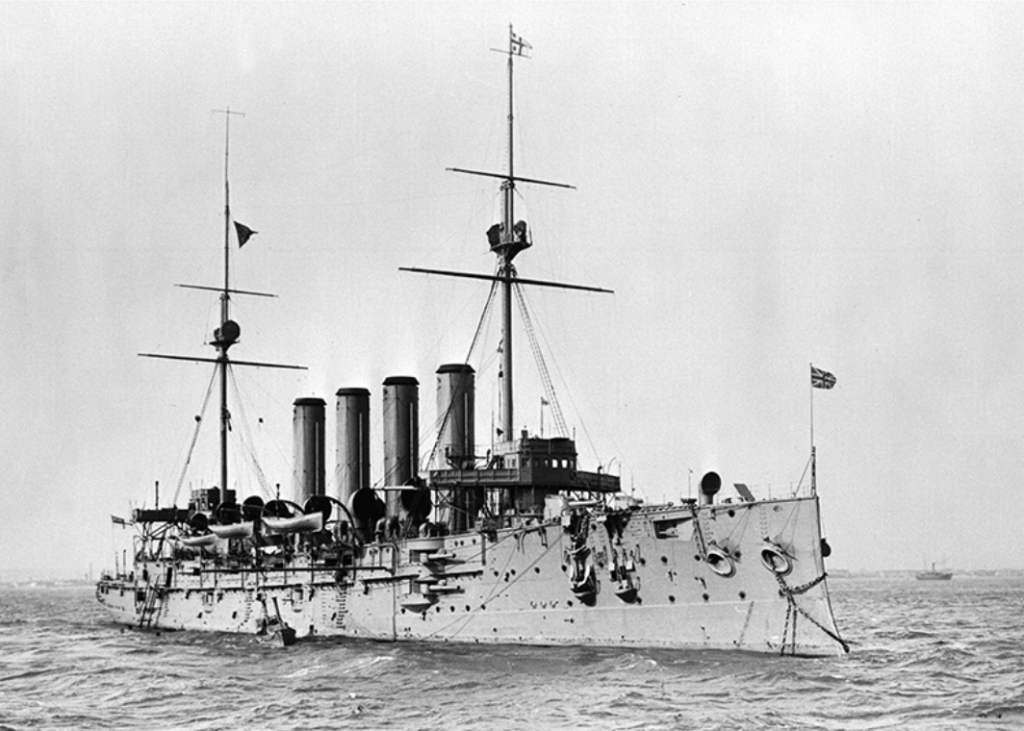

HMS Niobe was a Diadem class protected cruiser belonging to the Royal Navy. She was 462 feet and six inches long with a beam of 69 feet, and was powered by two steam powered shafts driving a four cylinder triple expansion engine creating 16,500 horsepower. This gave her a maximum speed of 20.5 knots. She would carry around 1,900 tons of coal as fuel. For armaments she had sixteen 6 inch guns, fourteen 12 pounder guns, three Hotchkiss guns and three torpedo tubes,

She had been laid down by the Vickers company at Barrow-in-Furness, so disappointingly for us there is no North-East coast connection to her origin that might have been connected to George’s interest. She was part of the Channel Squadron in the Boer War, then sent to Gibraltar to escort troop transports to the Cape where they could join the conflict. In December 1899, she and HMS Doris rescued troops from the SS Ismore which had run aground. The Ismore struck land that was hidden by a haze, and only eight of 129 horses on board were able to be saved, and all of the guns and ammunition aboard was lost. HMS Niobe saw further action in the Boer War, earning her crew the Queen’s South Africa Medal. At some point in her career she seems to have acquired a goat as ships mascot, as a photograph exists depicting the animal with the ship’s name clearly shown on headwear, with a navy sailor in the background.

HMS Niobe hit the news in the final two years of the Nineteenth Century for a handful of reasons. In January 1899 there was, as the newspapers put it, a ‘daring robbery’ in which the paymaster’s cabin was entered and £1,100 stolen (equivalent of over £86,000 today). During her sea trials she broke down three times, with another incident reported in March of 1899.

She continued in the service of the Royal Navy until 1910, whereupon she was traded to Canada to become part of the newly formed Canadian Navy along with HMS Rainbow, thereby becoming HMCS Niobe on 6th Sept that year. Prior to this she had been refitted to become a training ship. She arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 21st October, which was a careful decision as it was Trafalgar Day. She ran aground in fog off Cape Sable in July 1911, and was only saved through careful damage control. She needed six months of repairs after that and saw little service until the outbreak of the Fist World War at which point once again she became an escort for troop movements by sea.

By 1915 her funnels and boilers were badly worn out and bulkheads were in poor shape so in the September of that year she became a depot ship in Halifax. The Canadians sought to exchange her for a newer cruiser. 1917 brought further misfortune as an accident damaged a ship in a neighbouring berth. That ship, the SS Mont-Blanc was carrying munitions, which exploded, damaging Niobe in the process. Nonetheless she remained as a depot ship until 1920 when she was sold for scrap, and finally broken up in Philadelphia in 1922.

So, all in all a brief career for a vessel that on her launch day looked such a grand piece of naval engineering if the title image is anything to go by. It’s not at all certain which episode of her life inspired George to title a march after her – assuming we are correct, though there is much evidence from others of his pieces to support our hypothesis.

Niobe’s story did not end with her ultimate destruction, however. The significance of her role in the history of the Canadian Navy has ensured that the name Niobe lives on. She was, after all, the first large ship in that fledgling Royal Canadian Navy. Her name was given to a collection of scholarly papers collated in connection with that navy. Also, models and collections of artefacts relating to the Niobe can be found at several museums. The Naval Museum of Halifax had a room devoted to Niobe which includes her bell. Another legacy is that a corps of the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets in Nova Scotia bears the name RCSCC 62 Niobe.

During WW2, long after George’s death and the breaking up of the ship, the name Niobe returned to England where the Royal Canadian Navy’s destroyers were redeployed. A manning depot was needed, and the depot HMCS Dominion was renamed HMCS Niobe in 1941, and moved from Plymouth to Greenock as per the photograph shown.

In addition to the ship’s bell, another part of Niobe, one of her three anchors, was unearthed at the dockyard in Halifax in 2014. On the 17th October that year Canada announced that the 21st October, the day of her arrival in Halifax in 1910, would be named “Niobe Day.”

On that basis there is a possibility that this quick march, created by the pen of Shildonian blacksmith’s striker George Allan, might just have found a new significance. What better reason to play “Niobe” than to celebrate “Niobe Day.”